Lock Down Linux, Lock Out Threats

Lock Down Linux, Lock Out Threats

Learning the Linux File System Commands is important for moving around and managing files. The Linux file system is organized as one large hierarchy rooted at /. In fact, the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS), all files and directories appear under the root / directory That means / is the base of everything. Each directory under / has a special purpose – for example, /bin contains essential command binaries (like ls, cp, cat) needed by all users, and /home holds each user’s personal files and settings. Understanding this layout (FHS) and how permissions work will help you navigate without any problem. In this guide, we’ll cover basic navigation (cd, ls, pwd), file operations like (mkdir, rm, cp, mv, touch), and permissions like (chmod, chown), with examples and safety tips.

Image: The Linux file system hierarchy (root / and common sub-directories). The Linux file system is a single tree of directories, with / (root) at the base. All other directories branch off from /. For example, /bin holds binaries for essential commands (like ls, grep, etc.), /etc contains system-wide configuration files, and /home contains each user’s personal directory. Other common directories include /dev (device files), /boot (bootloader and kernels), /var (variable data such as logs), and /usr (shared user applications). Because of this standard layout, you’ll often find similar folders on different Linux distributions.

Image: In a normal Linux file manager view of the root (/) directory showing folders like bin, etc, home, etc. In a graphical file manager (as above), the root / directory shows all the main folders. For instance, /home/anand is the home directory for user “anand” and contains his files, for few files you have to manually allow to see the hidden files and directory.

To find your way around, start with a few key commands:

This prints the full path of your current directory ( /home/anand). Use pwd whenever you want to know your present working directory.

This command took you to /etc, no matter where you started (because /etc is an absolute path). To go up one level, use cd .. (the .. notation means parent directory. For instance, if you were in /home/anand/projects, running cd .. would move you to /home/anand.

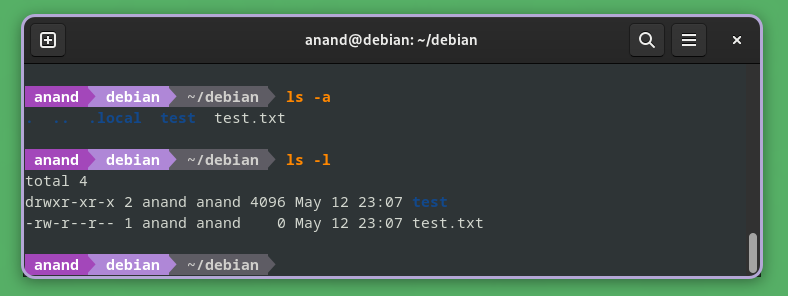

Once you know where you are, you can create, copy, move, and delete items:

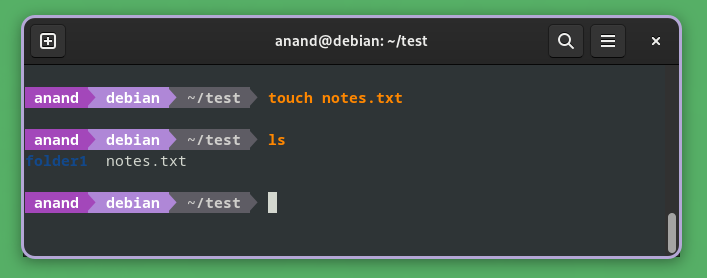

This made a new directory named folder1. You can create multiple levels at once with mkdir -p parent/child/grandchild if needed.

Now there’s a file named notes.txt (empty). You can also open a text editor (like nano notes.txt) to start writing in it.

All of these file commands respect the current directory unless you give an absolute path. For instance, ls file.txt looks in the current folder, while ls /home/anand/file.txt looks in your home directory. Always double-check paths (for example with pwd) to avoid accidentally affecting the wrong files

Linux files have permissions to control who can read, write, or execute them. Each file’s permissions are divided into three sets: user (u) – the file’s owner, group (g) – other users in the file’s group, and others (o) – everyone else. Each set has three rights: read (r), write (w), and execute (x) For example, a file with mode rwxr-xr– means: owner can read/write/execute, group can read/execute, others can read only. The numeric notation sums those rights (read=4, write=2, execute=1). So chmod 755 script.sh means owner gets 7 (4+2+1 = rwx) and group/others get 5 (4+0+1 = r-x).

To change these permissions, use chmod. You can use numeric mode as above, e.g. chmod 644 document.txt (owner=6, group=4, others=4), or symbolic mode like chmod u+x script.sh to add execute rights for the user. For example, chmod u+w file.txt lets the owner write to the file. Always be careful: do not chmod system files blindly, and only modify what you own or as root if necessary.

Each file also has an owner and group. The chown command changes these. For example, sudo chown anand notes.txt makes user anand the owner of file.txt. You often need sudo for this.

Remember that the root (administrator) user can override all permissions. the root user can modify or delete any file in any directory on the system. Therefore, use sudo (which grants temporary root privileges) only when needed.

Navigating and managing the file system is powerful, but with power comes responsibility. Keep these safety tips in mind:

By following these best practices, you’ll minimize accidents as you learn to use Linux file system commands confidently.